Introduction:

Copper may be needed in small doses, but managing it is no small task. It’s a mineral that must be absorbed efficiently, delivered precisely, and stored safely, or it can cause damage. Your body has a smart system for handling copper—and knowing how it works can help you understand why balance matters so much.

In this third article in the Copper Series, we’ll explore how copper gets from your plate to your cells, what affects its absorption, and how your body keeps it under control.

Copper Absorption: Where It Starts

Most copper is absorbed in the small intestine, especially in the duodenum and upper jejunum. Once digested from food, copper ions are transported into intestinal cells (enterocytes), where they join copper-carrying proteins.From there, copper enters the bloodstream, mostly bound to albumin and later handed off to the liver—the central hub for copper distribution and storage.

Key Player: Ceruloplasmin

Once in the liver, copper is either stored or packed into a special protein called ceruloplasmin, which delivers copper safely through the bloodstream to where it’s needed: tissues, enzymes, and cells.

Ceruloplasmin doesn’t just transport copper—it also helps oxidize iron, playing a crucial role in iron metabolism and red blood cell production.

How the Body Keeps Copper Levels Safe

Since too much free copper in the bloodstream can be toxic, your body has several layers of control:

- Tight regulation of absorption in the gut

- Storage in the liver, mostly bound to proteins like metallothionein

- Controlled release into circulation as needed

- Biliary excretion—excess copper is removed through bile and eliminated in the stool

These systems help prevent buildup, which is especially important because the body has no natural pathway for copper excretion through the kidneys.

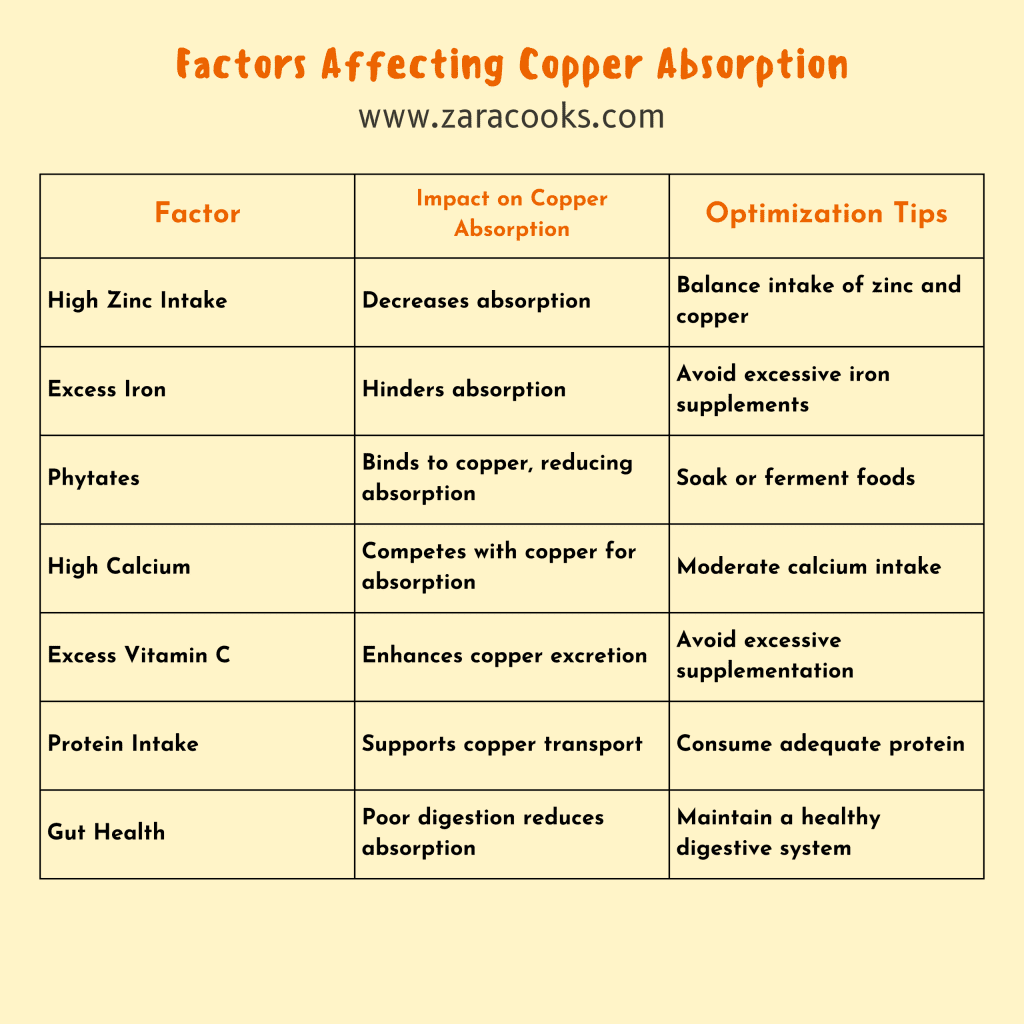

What Affects Copper Absorption?

Copper absorption is generally efficient—but a few factors can increase or decrease how well it’s absorbed.

Factors that Enhance Absorption:

- Sufficient stomach acid (copper needs an acidic environment to remain soluble)

- Moderate protein intake, which provides amino acids that help transport copper

- Presence of vitamin C and some amino acids, in moderate amounts

Factors that Inhibit Absorption:

- High zinc intake, especially from supplements (zinc competes with copper for absorption in the gut)

- Excessive iron supplementation

- Phytates (found in whole grains and legumes, though effect on copper is mild compared to iron or zinc)

- Certain genetic mutations (like ATP7A mutation in Menkes disease)

How Your Body Balances Copper

Copper homeostasis is mostly managed by two copper-transporting proteins:

- ATP7A – helps move copper from intestinal cells into the bloodstream

- ATP7B – helps load copper into ceruloplasmin in the liver and remove excess copper through bile

Mutations in these transporters cause rare but serious genetic disorders:

- Menkes disease – copper is absorbed poorly and trapped in intestinal cells

- Wilson’s disease – copper isn’t excreted properly, leading to dangerous buildup in the liver and brain

Summary Table: Copper Absorption and Regulation

| Step | What Happens |

| Absorption | In the small intestine (duodenum/jejunum) |

| Transport to liver | Via blood proteins like albumin and transcuprein |

| Storage | In liver, bound to metallothionein or ferritin |

| Main transporter protein | Ceruloplasmin (distributes copper to tissues) |

| Elimination | Excreted in bile and removed via stool |

| Disruptors | High zinc or iron, phytates, genetic conditions (Menkes, Wilson’s) |

Conclusion:

Your body works hard to make sure copper goes exactly where it’s needed—and nowhere else. But that balance is delicate. In our final article, we’ll share a list of the most copper-rich foods (both animal and plant-based), and how to eat to support healthy copper levels.